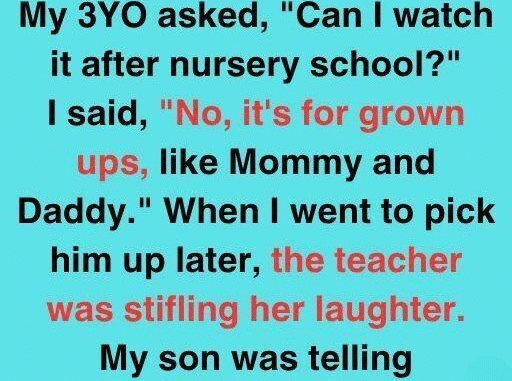

On my wife’s birthday, I gave her a wrapped DVD—Titanic—thinking a little romance, nostalgia, and Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet were always a good choice. As she unwrapped it, our three-year-old son, Max, tilted his head and asked, completely seriously, “Can I watch it after preschool?”

Without considering my words, I replied, “Not this one, buddy. That’s for grown-ups—just Mommy and Daddy.”

When I picked him up that afternoon, his teacher was struggling to contain her laughter. It turned out that from morning circle time until the end of the day, our sweet child had informed teachers, classmates, and several surprised parents that “Mommy and Daddy watch Titanic alone at night because it’s for grown-ups only.” I tried to clarify the situation at the classroom door.

“Just to be clear,” the teacher asked, her eyes sparkling with amusement, “this Titanic… the ship?”

I nodded, my face flushing. “With Leonardo DiCaprio.”

She finally released a chuckle. “Ah. We weren’t sure if it was… some other kind of Titanic.”

When I told my wife, she laughed so intensely she almost fell off the sofa. It became our favorite anecdote—a guaranteed way to get a laugh with little effort.

Beneath the humor, however, something else began to develop. Max became fascinated—not with the movie, but with the actual ship. The true story. Its immense size and its tragic end. He asked questions like a miniature historian.

“What made it sink? Did anyone live? Was there a slide? Was it like a pirate ship?”

His Duplo block constructions became ocean liners, complete with lopsided smokestacks and a shampoo-bottle iceberg. Bath time turned into a rescue mission with conditioner caps as lifeboats. It was endearing, and the interest didn’t disappear.

One night during dinner, he asked, “Daddy, why didn’t the captain see the iceberg?”

I attempted to simplify a complex idea for a preschooler. “Sometimes people believe they’re in control when they’re not,” I said. “They move too quickly and fail to see what’s coming.”

He nodded, as if filing the thought away. Then he whispered, “I think that’s what happened to you and Mommy.”

I was taken aback. “What do you mean, buddy?”

He looked at me with a gentle, unusual certainty. “When I was in Mommy’s tummy, you and her were going really fast. And you didn’t see your iceberg.”

The words felt like a shock of cold water. Max had been an unexpected pregnancy. We had been together for a year when the test was positive. We married quickly, purchased a small home, took stable jobs, and did our best to manage everything. We weren’t exactly unhappy. Just occupied. Living parallel lives. Co-captains on decks that seldom met.

That night, after Max was asleep, I told my wife what he had said. The warmth in her eyes faded.

“Oh.”

We finally had the discussion we had been avoiding for months—the kind you continually postpone while life continues around it. There was no shouting. No keeping score. Just acknowledging what we had both sensed: not unhappy, but disconnected. Moving fast. Overlooking what was right in front of us.

We implemented small adjustments. I left work early on Fridays and stopped checking email after dinner. She resumed painting—quiet afternoons where the house was filled with the smell of acrylics and coffee. We put our phones away more often. We agreed to walks and declined obligations we didn’t truly care about. Minor corrections to our course.

Meanwhile, Max continued being Max. The DVD collected dust. His interests shifted from ships to dinosaurs to volcanoes to black holes. His questions never lost their depth.

At five: “Why do you smile when you’re tired?”

At six: “Mommy, you should write a book about your dreams.”

At seven: “I think Grandpa visits me in my sleep. We talk without words.”

We called it imagination and kept the hallway light on.

When he turned nine, we found ourselves in Halifax—my wife for work, and Max still excited from a school lesson on Canada. We visited the Maritime Museum and accidentally found the Titanic exhibit.

Max became silent. He stood before a recovered deck chair as if it were a person. He traced the large wall map of the ship’s final hours and said, almost to himself, “Here. This is where it happened.”

“Did you learn that at school?” my wife asked.

He shook his head. “I just know.”

Back at the hotel, he asked if he could finally watch Titanic. He was ready. We agreed.

He barely moved, his eyes wide, his fists clenched. When it ended, he said quietly, “They were too proud. That’s why it sank.”

The next morning, I discovered a note on hotel stationery, in his neat handwriting: Even the largest ships need to be humble. Or else they will sink.

I placed it in my wallet.

He continued to develop his unique character. He preferred reading to video games, and conversation over noise. He formed a friendship with our elderly neighbors. I once found him in the yard with Mr. Holland—the solitary man who lived two doors down—both of them laughing. Later, I asked what they had discussed.

“He misses Mrs. Holland,” Max said. “He thinks no one remembers her. I told him to tell me everything. I said I’d remember.”

That winter, Mr. Holland passed away. At the funeral, they asked if anyone wished to speak. Max raised his hand. With shaking hands, he stood at the front and said, “I didn’t know Mr. Holland for very long. But I could tell he loved Mrs. Holland because his smile changed when he talked about her. I think she knew.”

There wasn’t a dry eye in the room. Including mine.

By thirteen, my wife and I had changed as well. We switched careers. We began volunteering. We simplified our lives in the best ways—smaller social circles, deeper connections. We learned to identify our icebergs, not just crash into them.

Max joined a mentorship program—not because he needed guidance, but because he wanted to offer it. One evening, I picked him up, and he was quiet in the car, looking more mature in the way children do when they’ve been observing closely.

“How did it go?”

“Good.” A pause. “One kid’s dad left. I told him mine stayed.” He looked at me. “Sometimes staying is harder than leaving. Thanks for staying, Dad.”

I had to pull the car over. Tears have their own timing.

High school came and went. College, too. Max studied psychology. “People are like ships,” he said once. “Some drift. Some sink. Some anchor too deep. But all carry stories.”

On the day he graduated, he presented us with a gift. A DVD case.

We opened it: Titanic. The same copy we had bought all those years before. Inside, a note:

Thank you for steering me through life—even when we couldn’t see the icebergs. —Max, your first crewmate.

We cried. We embraced. We laughed like we used to. That night, we finally watched Titanic again. Just us. Without rushing. We watched every minute of the film—and, in a way, every minute of the past decade woven through it. The near-disasters. The changes in direction. The quiet rescues.

When the credits rolled, my wife leaned against me. “It’s funny,” she said. “The thing that once made us laugh now feels like what brought everything full circle.”

Because sometimes the iceberg isn’t the conclusion. Sometimes it’s the moment you begin to navigate with your heart.

If there is a lesson, it’s this: don’t try to outrun your storms. Don’t disregard the warnings because the deck looks attractive and the band is still performing. Remain humble, even when you feel invincible. And never underestimate the quiet insight of the small people observing you from their booster seats—they perceive more than we realize.

If this story resonated with you, share it. Someone out there is heading quickly toward an iceberg. Perhaps this is the gentle push that helps them decelerate.

Even the largest ships need to be humble. Or else… they will sink.